By Dr. Nataliya D. Brantly

U.S. healthcare has changed significantly since the early 2000s. This change was spurred by a number of studies that documented and exposed systemic failures, inefficiencies, poor coordination, and inadequate patient-centered care.[1]High levels of medical errors in a clinical setting, contributing to the thousands of deaths annually, emphasized the need to prioritize patient safety.[2] Additional concerns for the U.S. include healthcare spending, which ranks first globally, and healthcare coverage, which ranks last among high-income countries.[3] Emma Wager et al. estimate that the U.S. spends, on average, twice as much per person on healthcare as other high-income countries.[4] The U.S. healthcare spending continues to grow. In 2023, it was estimated to grow by 7.5 percent, reaching $14,570 per person or a cumulative spending of $4.9 trillion.[5] Policymakers, researchers, and healthcare professionals have turned towards digital health and efforts of automation to address and eliminate issues associated with healthcare inefficiencies, spending and patient safety.

A number of studies were published emphasizing the benefits of health IT, such as the adoption of electronic health record systems (EHR). For example, a 2006 systemic review demonstrated the advantages of EHR systems over paper records and the improvements to the quality and efficiency of care with the implementation of health IT in select institutions.[6] Most importantly, the digitalization of healthcare was associated with a decrease in annual healthcare spending. Richard Hillestad et al. wrote about the transformative power of widespread EHR adoption that could lead to annual savings of $81 billion, with the possibility of doubling these savings through the use of health IT for chronic disease prevention and management.[7] By 2008, the adoption of EHR by acute care hospitals was low despite the consensus that health IT use should result in “more efficient, safer, and higher-quality care.”[8] These studies and conclusions led to the belief that issues within healthcare can be resolved through the adoption of health technologies.

EHRs emerged as a solution to improve quality and reduce errors, enhance efficiency, and surveillance, and improve patient outcomes. The Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act was enacted as part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) of 2009 on February 17, 2009, to incentivize the meaningful use of EHRs and strengthen the privacy and security provisions of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996. HIPAA establishes federal standards protecting sensitive health information from disclosure without the patient’s consent. Section 13402(e)(4) of the HITECH Act mandates covered entities and their business associates to report breaches of unsecured protected health information (PHI) affecting 500 or more individuals. The first breach report was submitted on October 21, 2009. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office for Civil Rights makes the breach portal public. The information below is the result of the data analysis of reported breaches of unsecured PHI that were reported to the HHS Secretary from 2013 through 2023.[9]

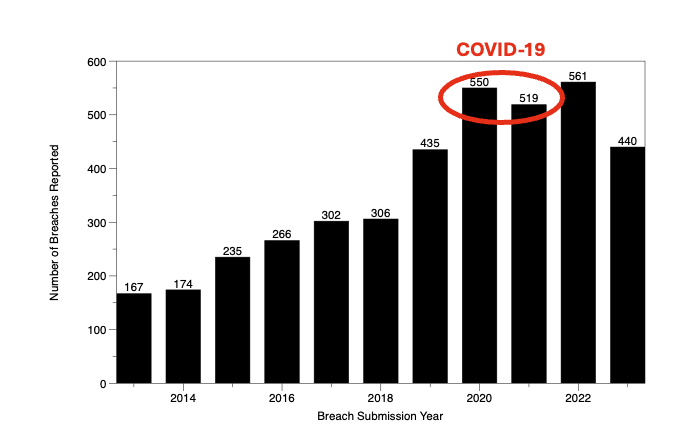

Figure 1. Number of reported breaches of unprotected PHI annually, 2013-2023

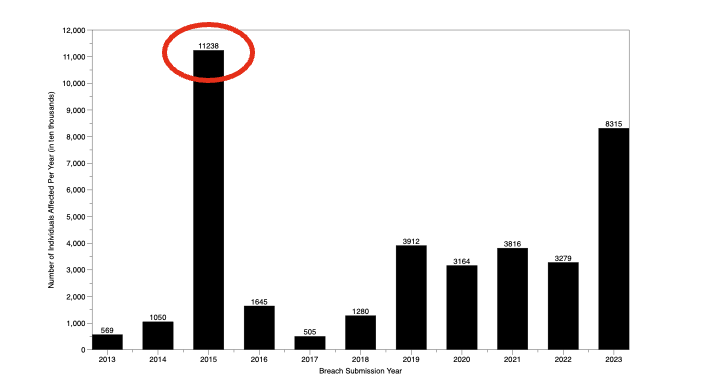

The data reveal that from the beginning of 2013 through the end of 2023, 4,994 breaches of unsecured PHI were reported to the HHS Secretary by covered entities and business associates, impacting over 461.7 million individuals. Upon cleaning the data to remove duplicates and erroneous reports, the dataset was reduced from 4,994 to 4,186 reported breaches, impacting a total of over 387.7 million individuals from 2013 through the end of 2023. Figure 1 above highlights the number of annual breaches of unprotected health information and demonstrates a steady increase in the number of reported incidents. The number of breaches peaked during COVID-19 with the increased use of telehealth and telemedicine technologies but did not prop to pre-pandemic levels following 2021. Figure 2 that follows illustrates the number of individuals affected through reported breaches of unprotected PHI annually. A single event is responsible for the spike in 2015. On March 13, 2015, Anthem, Inc., a health insurance provider, reported a breach of PHI due to an advanced persistent threat attack, an undetected continuous and targeted cyberattack for the apparent purpose of extracting data. This led to the largest U.S. health data breach in history and exposed the electronic PHI of almost 79 million people.

Figure 2. Number of individuals affected through breaches of unprotected PHI annually,

2013-2023

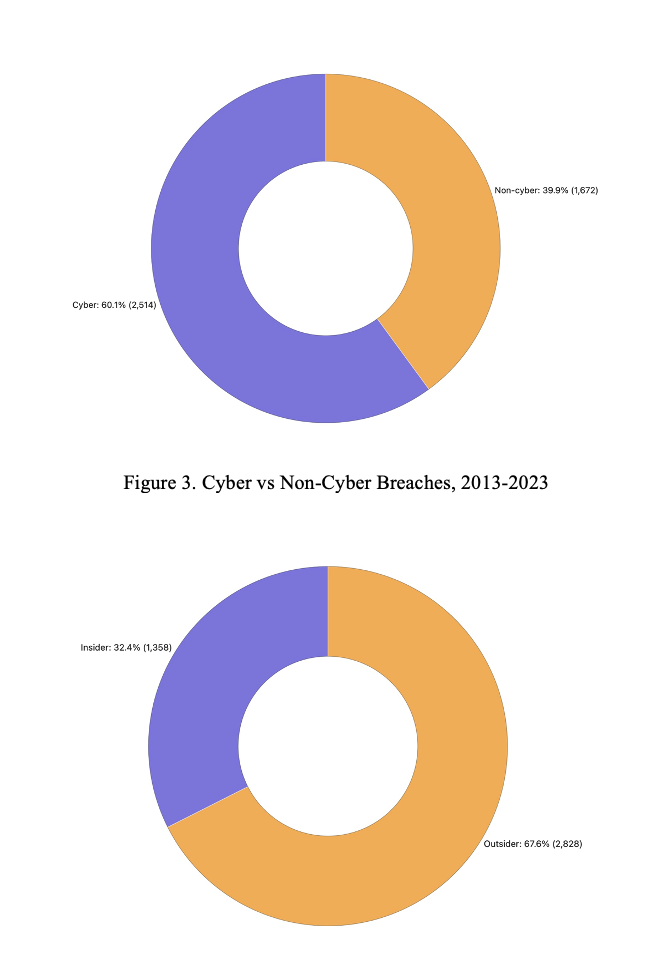

The U.S. healthcare system has undergone important changes with advancements in Health IT that came along with the growing global threats. This is reflected in a steady increase in cyber-related crimes targeting healthcare since 2013. In addition to the increasing number of breaches of unprotected PHI, the proportion of cyber-related breaches has increased from 15.3% in 2013 to 79.2% in 2023. The total number of cyber-related breaches constitutes 60.1% of all reported breaches from 2013 to 2023, as illustrated in Figure 3. The U.S. healthcare system is also experiencing a growing number of external threats, from 44.6% in 2023 to 80% in 2023. External threats, which include ransomware attacks, email phishing, digital data breaches, and burglaries, constitute 67.6% of the total breaches reported from 2013 to 2023. This means that the origins and types of threats to PHI create additional challenges and add to the complexity of efforts aimed at securing protected patient health information.

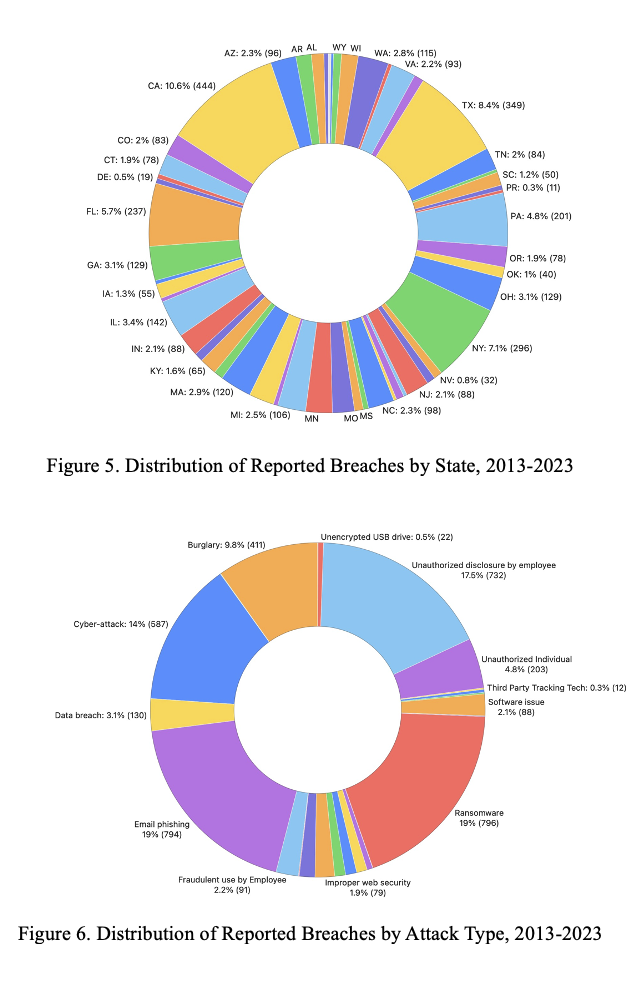

Reports of breaches of unprotected PHI come from every U.S. state. The greatest number of reports originated from California (10.6%, 444 breaches), Texas (8.4%, 349 breaches), New York (7.1%, 296 breaches), Florida (5.7%, 237 breaches), and Pennsylvania (4.8%, 201 breaches) as illustrated in Figure 5 below. Ransomware (796 breaches) and phishing emails (794 breaches) are the primary cyber threats impacting U.S. healthcare (Figure 6). in health care. The engagement of healthcare providers with third-party vendors and third-party technologies led to the emergence of a new threat, which further adds to the complexity of PHI security. In 2022 the first instances have emerged of third-party tracking technologies becoming the cause of PHI breaches.

The data highlights significant vulnerabilities in the U.S. healthcare system’s handling of protected health information. Every reported breach involved the loss of personal data, with 21.9% exposing financial information and 86% compromising health records. Additionally, business associates were responsible for 30.3% of breaches, affecting 117.5 million individuals. A business associate is a person who provides legal, accounting, consulting, management, administrative, financial, and other services to or for a Covered Entity that necessitates the disclosure of individually identifiable health information. These breaches emphasize the complex web of entities involved in managing sensitive health data and the risks associated with its widespread digitalization.

While technological advancements have addressed some inefficiencies, such as the storage and security of paper records, they have also introduced new challenges and burdens. The threats to PHI are growing with increasing outsider threats, growing in scope and scale of breaches. Additionally, the burdens and responsibilities for PHI are shifting. Valid concerns exist with greater digitalization and automation of the U.S. healthcare system: greater trust and overreliance on health IT, dehumanization of care, and erosion of clinical competence with increased reliance on Artificial Intelligence (AI). Increasing and largely unresolved issues pertaining to the security of electronic PHI are met with efforts to make the data available to different stakeholders, both patients and providers, who need to be able to access the data. Greater automation and EHR interoperability, as the next step in the development of digital health in the U.S. likewise will address some issues but will also create new ones.

America., Institute of Medicine (U.S.). Committee on Quality of Health Care in. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, D.C: National Academy Press, 2001.

Chaudhry, Basit, Jerome Wang, Wu Shinyi, Margaret Maglione, Walter Mojica, Elizabeth Roth, Sally Morton, Paul G. Shekelle, and John D. Halamka. “Systematic Review : Impact of Health Information Technology on Quality, Efficiency, and Costs of Medical Care.” Annals of Internal Medicine 144, no. 10 (May 16, 2006): 742–752. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-144-10-200605160-00125.

CMS. “National Health Expenditure Data: Historical.” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, December 18, 2024. https://www.cms.gov/data-research/statistics-trends-and-reports/national-health-expenditure-data/historical.

Donaldson, Molla S, Janet M Corrigan, and Linda T Kohn. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. 1st ed. Washington, D.C: National Academies Press, 2000.

HHS. “Breach Portal: Notice to the Secretary of HHS Breach of Unsecured Protected Health Information.” HHS Archive, January 14, 2025. https://ocrportal.hhs.gov/ocr/breach/breach_report.jsf.

Hillestad, Richard, James Bigelow, Anthony Bower, Federico Girosi, Robin Meili, Richard Scoville, and Roger Taylor. “Can Electronic Medical Record Systems Transform Health Care? Potential Health Benefits, Savings, And Costs.” Health Affairs 24, no. 5 (2017): 1103–17. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.24.5.1103.

K., Jha Ashish, DesRoches Catherine M., Campbell Eric G., Donelan Karen, Rao Sowmya R., Ferris Timothy G., Shields Alexandra, Rosenbaum Sara, and Blumenthal David. “Use of Electronic Health Records in U.S. Hospitals.” New England Journal of Medicine 360, no. 16 (2009): 1628–38. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmsa0900592.

Lorenzoni, Luca, Annalisa Belloni, and Franco Sassi. “Healthcare Expenditure and Health Policy in the USA versus Other High-Spending OECD Countries.” The Lancet 384, no. 9937 (2014): 83–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(14)60571-7.

Wager, Emma, Matthew McGough, Shameek Rakshit, Krutika Amin, and Cynthia Cox. “How Does Health Spending in the U.S. Compare to Other Countries?” Health System Tracker, January 23, 2025. https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/chart-collection/health-spending-u-s-compare-countries/#Health.

[1] Institute of Medicine (U.S.). Committee on Quality of Health Care in America., Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century (Washington, D.C: National Academy Press, 2001).

[2] Molla S Donaldson, Janet M Corrigan, and Linda T Kohn, To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System, 1st ed. (Washington, D.C: National Academies Press, 2000).

[3] Luca Lorenzoni, Annalisa Belloni, and Franco Sassi, “Health-Care Expenditure and Health Policy in the USA versus Other High-Spending OECD Countries,” The Lancet 384, no. 9937 (2014): 83–92, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(14)60571-7.

[4] Emma Wager et al., “How Does Health Spending in the U.S. Compare to Other Countries?,” Health System Tracker, January 23, 2025, https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/chart-collection/health-spending-u-s-compare-countries/#Health.

[5] CMS, “National Health Expenditure Data: Historical,” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, December 18, 2024, https://www.cms.gov/data-research/statistics-trends-and-reports/national-health-expenditure-data/historical.

[6] Basit Chaudhry et al., “Systematic Review : Impact of Health Information Technology on Quality, Efficiency, and Costs of Medical Care.,” Annals of Internal Medicine 144, no. 10 (May 16, 2006): 742–752, https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-144-10-200605160-00125.

[7] Richard Hillestad et al., “Can Electronic Medical Record Systems Transform Health Care? Potential Health Benefits, Savings, And Costs,” Health Affairs 24, no. 5 (2017): 1103–17, https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.24.5.1103.

[8] Jha Ashish K. et al., “Use of Electronic Health Records in U.S. Hospitals,” New England Journal of Medicine 360, no. 16 (2009): 1628–38, https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmsa0900592.

[9] HHS, “Breach Portal: Notice to the Secretary of HHS Breach of Unsecured Protected Health Information.,” HHS Archive, January 14, 2025, https://ocrportal.hhs.gov/ocr/breach/breach_report.jsf.