Haleigh Horan and Divine Tsasa Nzita

Ransomware attacks have become more common over the past several years and there has been a prominent spike in ransomware attacks against the education sector. As schools and school districts increase their use of technology across their enterprise operations they are increasingly viewed as potential targets with critical resources, student, or employee data.

The Chronicle of Higher Education in collaboration with Palo Alto Networks found in 2022 that data indicates that 1,436 schools and colleges were affected after 65 separate ransomware attacks took place which affected around 1,074,926 students.[1] These attacks are estimated to have resulted in $9.45 billion in downtime related costs.[2] Many schools or universities struggle to recover from attacks. Disruption time varies institution by institution. When an attack disrupts student data access this affects collegiate applications, financial aid decisions and more. Schools that lose access to student records, attendance, and even financial aid reports can hinder or delay a student’s graduation or the provision of records necessary for continuing education or employment opportunities. In addition to conventional ransom tactics, firms are also switching to double-extortion tactics which seek to add insult to injury by threatening to leak student information if a ransom isn’t paid.[3]

Ransomware attacks affect schools at all levels in many ways. Reputational damage tarnishes a school’s reputation and can lead to loss of trust from their students, parents, and partner organizations and institutions. Attacks are also thought to potentially impact enrolment and retention rates.[4] The fear of reputational damage often forces schools to pay attackers.[5] One study found that targeted universities frequently paid more than $400,000 in payment, with the University of California system paying a $1.14 million ransom in 2020.[6] A failure to pay a ransom might also result in civil or criminal proceedings from students or employees whose data has been compromised or disclosed.

To determine the scope of how ransomware is affecting schools, we examined two sources of state-level data on the number of attacks and the number of students affected. Additionally, we examined whether universities or K-12 institutions more frequently they were public or private institutions. The data indicate that larger states, in particular Texas, experienced the greatest frequency of ransomware attacks. Texas was attacked 83 times within our dataset. Combined data from 28 of the 83 attacks indicate that 421,808 individuals’ data records were impacted. The data indicates that Nevada experienced only two attacks, yet due to the size of its districts, 338,025 student records were affected.

Almost all 50 states have fallen victim to cyberattacks and this has only increased after the COVID-19 pandemic. Larger states like Texas and California are often victims of these attacks in comparison to smaller states, leading students and families concerned about their information being leaked online. One school district, Lost Angeles Unified School District, fell victim to an attack in September of 2022. From this attack, the breech “exposed student psychological evaluations, detailed medical histories, academic performance and disciplinary records.”[7] The release of this information can have profound effects on children for decades to come, which is evident from a separate cyberattack that took place against Minneapolis Public Schools. After the attack against Minneapolis Public Schools, students began pleading with their district to do something regarding their files that had been leaked. This attack caused so much emotional trauma that they would wet the bed or cry themselves to sleep. Another school district that faced a significant cyberattack was Judson Independent School District in Texas. In this case, the district wasn’t transparent about the data the attackers stole. From this attack, parents expressed concern as their and their student’s information is in the system, social security numbers and bank information are also listed, and some even expressed concern that their children’s bus stop location was taken.

These two cases only highlight the impacts that students and families face when their schools are affected by a ransomware attack. Often, learning is halted when these incidents occur, ranging from three days to three weeks. In addition, the recovery time substantially impacts everyone involved, as it can take two to nine months. Lastly, school districts face monetary losses “ranging from $50,000 to $1 million.”[8] However, these costs are necessary to replace hardware affected by the attack and implement protocols to prevent future attacks. A common theme between all cases was that school administrators failed to inform parents and students about the incidents in a timely manner. Although this is a major issue, currently, there is “no federal law to require this notification from schools.”[9] In the case surrounding Minneapolis, one family didn’t even know that they were a victim of the ransomware attack until a news reporter contacted them.

It is evident that schools and state and federal governments are not doing enough to prevent these attacks and the release of information. The federal government has provided $1 billion in cybersecurity grants for the next four years. In the case of Minnesota, their state received $18 million, which is to be spread amongst “3,600 different entities,” which is also to be shared with “cities and tribal governments.”[10] In addition, “$22.5 million” was provided by state officials “for cyber and physical security in schools.”[11] To try and ensure that schools have enough funding since recovery from ransomware attacks is so expensive, many are trying to “tap a federal program called E-Rate that is designed to improve broadband connections to schools and libraries.”[12] Ultimately, schools are being harmed by a lack of funding and resources to ensure that they are protected from various ransomware groups. Additionally, families and children needs are not being addressed because ransomware attacks often go unseen for months at a time and because of the lack of communication once an attack takes place. Moving forward, it is imperative that schools and government officials work together to ensure sufficient funding and procedures are put in place to protect vulnerable children and their families.

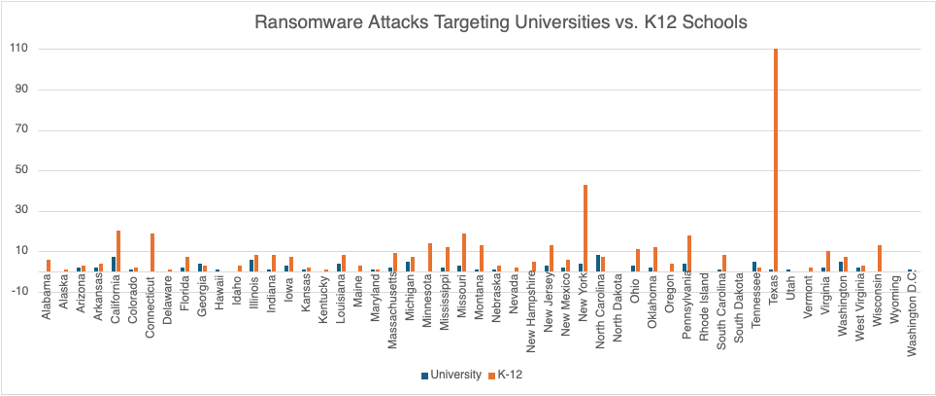

Figure 1: Comparison of the Number of Ransomware Attacks Against Universities and K-12 Schools

Figure 1 shows how ransomware attacks varied between universities and K-12 schools. The graph shows that Texas, California, New York, and Michigan faced the most ransomware attacks. Other states, like North Dakota, Rhode Island, South Dakota, and Wyoming, faced zero ransomware attacks. Additionally, it can the number of ransomware attacks against K-12 schools exceeded those of universities across most states. The Maryland is an outlier with universities and K-12 institutions suffering the same number of attacks. Tennessee, Utah, and Washington D.C. all experienced more attacks against universities than K-12 schools.

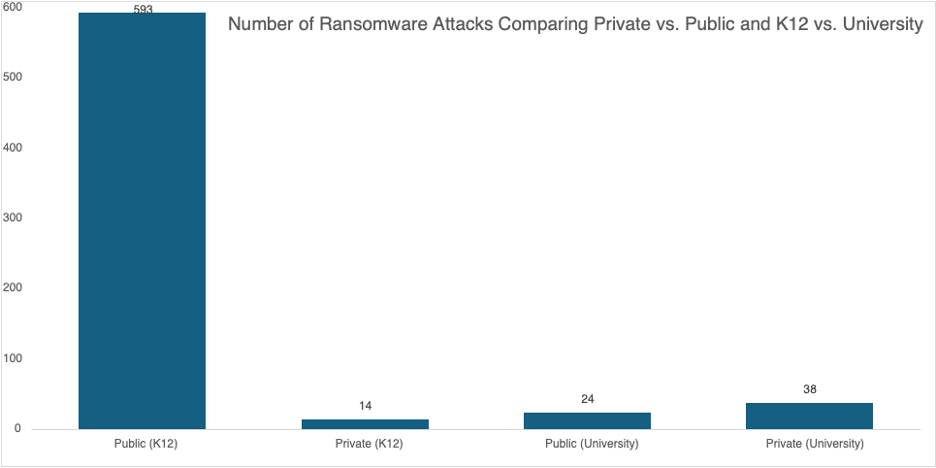

Figure 2 : Ransomware Attacks by Institution Type

Figure 2 compares the number of ransomware attacks that took place against K-12 schools and Universities. Additionally, the data were broken down by institution type, to determine whether public or private institutions were affected more by ransomware attacks. Based on the data, it was concluded that public K-12 schools were affected more frequently than comparable private K-12 schools, private universities, and public universities. Private universities were targeted more by ransomware attacks more frequently than public universities. It could be assumed that public schools are affected more because they have more students, thus more data, providing attackers with more information. For private universities, it can be assumed that they are affected slightly more than public universities since they may have less stringent data protection processes because of their enrollment size or because they lack the funding to provide protective services. Because of this, it would be beneficial for public schools and private universities to invest more in protecting their networks and data storage systems.

To conclude, ransomware attacks are on the rise against educational institutions and other important organizations like hospitals and police stations. All 50 states and the District of Columbia are affected. K-12 schools were affected more than universities. The data shows now clear differentiation between public and private institutions. Ransomware techniques are evolving and will increasingly requires schools to implement better network and data protection plans.

References

Anft, M. (n.d.). An emerging threat: Ransomware – The chronicle of higher … An Emerging Threat: Ransomware. https://connect.chronicle.com/rs/931-EKA-218/images/EmergingThreat_TrendSnapshot.pdf

Bajak , Frank, Heather Hollingsworth , and Larry Fenn. “Ransomware Criminals Are Dumping Kids’ Private Files Online after School Hacks.” The Press Democrat, July 5, 2023. https://www.pressdemocrat.com/article/news/ransomware-criminals-are-dumping-kids-private-files-online-after-school-ha/.

Bischoff, P. (2023, July 4). Ransomware attacks on US schools and colleges cost $9.45bn. Comparitech. https://www.comparitech.com/blog/information-security/school-ransomware-attacks/

Bischoff, Paul. “Ransomware Gang Says It Hacked a Virginia School District, Stole Data.” Comparitech, March 7, 2025. https://www.comparitech.com/news/ransomware-gang-says-it-hacked-a-virginia-school-district-stole-data/.

Butt, U., Yusuf Dauda, & Baba Shaheer. (2023). Ransomware Attack on the Educational Sector. Advanced Sciences and Technologies for Security Applications, 279–313. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-33627-0_11

“Information about Cybersecurity Incident.” Fairfax County Public Schools. Accessed March 17, 2025. https://www.fcps.edu/information-about-cybersecurity-incident#:~:text=Fairfax%20County%20Public%20Schools%20(FCPS,systems%2C%20and%20restore%20affected%20servers.

Keierleber, Mark. “Kept in the Dark: Meet the Hired Guns Who Ensure School Cyberattacks Stay Hidden.” The 74, February 4, 2025. https://www.the74million.org/article/kept-in-the-dark/?utm_source=The%2B74%2BMillion%2BNewsletter&utm_campaign=136396826d-EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_2022_07_27_07_47_COPY_01&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_077b986842-136396826d-49062689#sp_container.

Lee, Hunter. “Glendale School District Recovering from Cyber Attack.” GovTech, December 11, 2023. https://www.govtech.com/education/k-12/glendale-school-district-recovering-from-cyber-attack.

Lingle , Brandon. “Over 26,000 Impacted by Ransomware at Texas School District.” GovTech, June 25, 2021. https://www.govtech.com/over-26-000-impacted-by-ransomware-at-texas-school-district.

Meland, P. H., Bayoumy, Y. F. F., & Sindre, G. (2020). The Ransomware-as-a-Service economy within the darknet. Computers & Security, 92, 101762. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cose.2020.101762

Fouad, N. (2021, September 11). Securing higher education against cyberthreats: from an institutional risk to a national policy challenge. Taylor & Francis Online. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/23738871.2021.1973526

Hess, F. (2023, September 21). The top target for ransomware? it’s now K-12 schools. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/frederickhess/2023/09/20/the-top-target-for-ransomware-its-now-k-12-schools/?sh=7411840f563f

Håkon Meland, P., Fareed Fahmy Bayoumy, Y., & Sindre, G. (2020, February 29). The ransomware-as-a-service economy within the darknet. Computers & Security. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0167404820300468

The K12 Cyber Incident Map. K12 SIX. (n.d.). https://www.k12six.org/map

Kapko, Matt. 2022. “Los Angeles Schools’ Data Leaked After Ransomware Attack.” Cybersecurity Dive (Oct 03). http://login.ezproxy.lib.vt.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/trade-journals/los-angeles-schools-data-leaked-after-ransomware/docview/2723289033/se-2.

Kumar , J. (2023, December 7). Enhancing Public Awareness and Education of Ransomware Attacks. https://d197for5662m48.cloudfront.net/documents/publicationstatus/180686/preprint_pdf/0bfc9779916cd40637a51df6274120d0.pdf

Langreo, L. (2023, August 18). Schools are a top target of ransomware attacks, and it’s getting worse. Education Week. https://www.edweek.org/technology/schools-are-a-top-target-of-ransomware-attacks-and-its-getting-worse/2023/08

Levi, R. (2023, October 20). Ransomware attacks against hospitals put patients’ lives at risk, researchers say. NPR; Guest. https://www.npr.org/2023/10/20/1207367397/ransomware-attacks-against-hospitals-put-patients-lives-at-risk-researchers-say#:~:text=Ransomware%20attacks%20in%20health%20care%20more%20than%20doubled

McChristian, T. (2023, July 10). Held for ransom: What schools need to know before a ransomware attack. Technology Solutions That Drive Education. https://edtechmagazine.com/k12/article/2022/10/held-ransom-what-schools-need-know-ransomware-attack#:~:text=The%20best%20protection%20against%20ransomware%20is%20a%20combined,as%20strong%20identity%20management%20within%20their%20IT%20environment

Meland, P. H., Bayoumy, Y. F. F., & Sindre, G. (2020). The Ransomware-as-a-Service economy within the darknet. Computers & Security, 92, 101762. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cose.2020.101762

Office, U.S. Government Accountability. “Data Security: Recent K-12 Data Breaches Show That Students Are Vulnerable to Harm.” Data Security: Recent K-12 Data Breaches Show That Students Are Vulnerable to Harm | U.S. GAO, December 1, 2022. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-20-644.

Orchison, M. (2023, May 19). How cyber attackers get into a school. 9ine. https://www.9ine.com/newsblog/how-cyber-attackers-get-into-a-school#:~:text=One%20primary%20way%20in%20which,has%20unknowingly%20downloads%20a%20malware.

Riley, Stan. 2022. “Independent School Districts in Texas: A Focused Ethnography on Cybersecurity Barriers.” Order No. 28965030, Northcentral University. http://login.ezproxy.lib.vt.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/independent-school-districts-texas-focused/docview/2642235615/se-2.

Uberti, David. 2020. “Hackers Smell Blood as Schools Grapple with Virtual Instruction; Tech Staff Struggle to Ward Off Attacks, Including Ransom Demands.” WSJ Pro.Cyber Security (Oct 19). http://login.ezproxy.lib.vt.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/trade-journals/hackers-smell-blood-as-schools-grapple-with/docview/2451747654/se-2.

“Virginia’s Largest School System Hit with Ransomware.” Virginia’s Largest School System Hit With Ransomware. Accessed March 17, 2025. https://www.darkreading.com/cyberattacks-data-breaches/virginia-s-largest-school-system-hit-with-ransomware.

[1] Bischoff, P. (2023, July 4). Ransomware attacks on US schools and colleges cost $9.45bn. Comparitech. https://www.comparitech.com/blog/information-security/school-ransomware-attacks/

[2] Bischoff, P. (2023, July 4). Ransomware attacks on US schools and colleges cost $9.45bn. Comparitech. https://www.comparitech.com/blog/information-security/school-ransomware-attacks/

[3] Bischoff, P. (2023, July 4). Ransomware attacks on US schools and colleges cost $9.45bn. Comparitech. https://www.comparitech.com/blog/information-security/school-ransomware-attacks/

[4] Butt, U., Yusuf Dauda, & Baba Shaheer. (2023). Ransomware Attack on the Educational Sector. Advanced Sciences and Technologies for Security Applications, 279–313. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-33627-0_11

[5] Butt, U., Yusuf Dauda, & Baba Shaheer. (2023). Ransomware Attack on the Educational Sector. Advanced Sciences and Technologies for Security Applications, 279–313. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-33627-0_11

[6] Fouad, N. (2021, September 11). Securing higher education against cyberthreats: from an institutional risk to a national policy challenge. Taylor & Francis Online. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/23738871.2021.1973526

[7]Keierleber, Mark. “Kept in the Dark: Meet the Hired Guns Who Ensure School Cyberattacks Stay Hidden.” The 74, February 4, 2025. https://www.the74million.org/article/kept-in-the-dark/?utm_source=The%2B74%2BMillion%2BNewsletter&utm_campaign=136396826d-EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_2022_07_27_07_47_COPY_01&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_077b986842-136396826d-49062689#sp_container.

[8] Office, U.S. Government Accountability. “Data Security: Recent K-12 Data Breaches Show That Students Are Vulnerable to Harm.” Data Security: Recent K-12 Data Breaches Show That Students Are Vulnerable to Harm | U.S. GAO, December 1, 2022. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-20-644.

[9] Bajak , Frank, Heather Hollingsworth , and Larry Fenn. “Ransomware Criminals Are Dumping Kids’ Private Files Online after School Hacks.” The Press Democrat, July 5, 2023. https://www.pressdemocrat.com/article/news/ransomware-criminals-are-dumping-kids-private-files-online-after-school-ha/.

[10] Bajak , Frank, Heather Hollingsworth , and Larry Fenn. “Ransomware Criminals Are Dumping Kids’ Private Files Online after School Hacks.” The Press Democrat, July 5, 2023. https://www.pressdemocrat.com/article/news/ransomware-criminals-are-dumping-kids-private-files-online-after-school-ha/.

[11] cities and tribal governments

[12] Bajak , Frank, Heather Hollingsworth , and Larry Fenn. “Ransomware Criminals Are Dumping Kids’ Private Files Online after School Hacks.” The Press Democrat, July 5, 2023. https://www.pressdemocrat.com/article/news/ransomware-criminals-are-dumping-kids-private-files-online-after-school-ha/.