By Ethan Dettman

As cyber threats become more and more prevalent today, Chinese threat actor groups employ many malware packages to obtain information, both for personal gain and the benefit of the Chinese state. One of the most prevalent packages is Shadowpad, which has been used since 2017. Shadowpad is privately shared among Chinese-linked threat actor groups and is a modular malware that can add and remove different functionality through plugins. The malware is deployed using DLL sideloading and is mainly used for espionage operations by Chinese hackers-for-hire in service of the Chinese state. This blog post will discuss what Shadowpad is, how it is deployed, and usage cases of the malware along with why it is so dangerous.

What is Shadowpad?

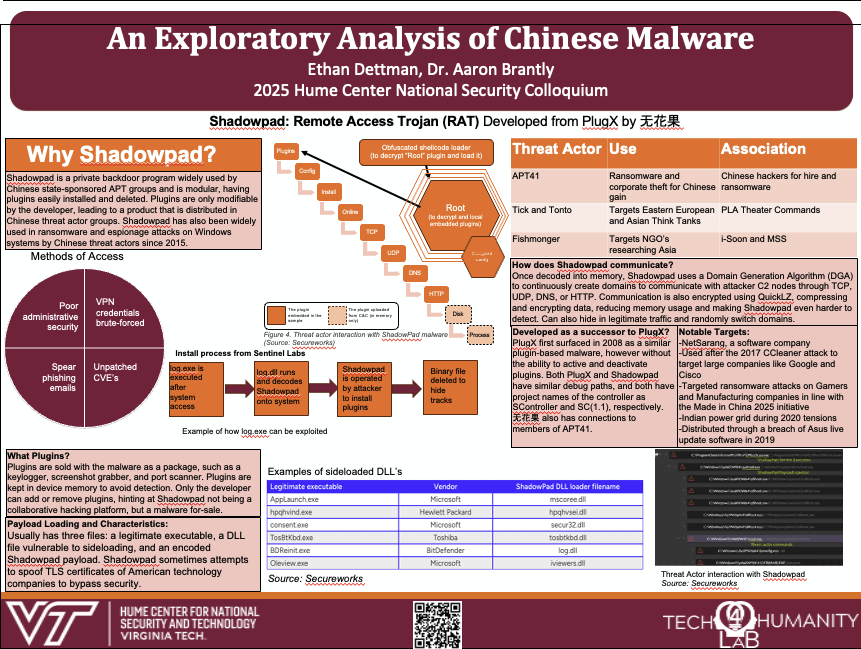

Shadowpad is a modular malware framework that leverages DLL sideloading to load the Shadowpad shellcode, which establishes contact with the attacker, and then custom malware plugins are loaded onto the infected Windows system. The malware is sold privately in custom packages, with specific plugins being added or removed based on how much the client pays for the software.[1] The plugins have many functions that will be discussed later, but the plugins are what makes Shadowpad so dangerous, as functionality can be removed or loaded onto Shadowpad remotely. The attacker can control the malware through a Command and Control (C2) server that uses protocols like TCP and HTTP to operate Shadowpad and receive information.[2]

How Shadowpad Works

Analyzing Shadowpad can be difficult, owing to the obfuscation methods employed on the code. The malware also runs almost entirely in Remote Access Memory, or RAM leaving few traces if not caught while active. Once active, Shadowpad loads the necessary files from memory, bypassing most anti-virus disk scans. Shadowpad is first inserted onto a system, which in past attacks has come from poor password security, access to a company’s VPN system, spear phishing emails, and exploited software distributed with malware attached.[3] To boot the malware, DLL sideloading is abused. A DLL, or Dynamic Link Library, is a shared library of executable code that Windows uses to reduce the usage of repetitive code and increase performance.[4] Unlike a .exe file, a DLL needs to be called to execute by another program. For example, Windows has a shared DLL named user32.dll that is used by all Windows programs to enable popups to occur. This way, not every Windows developer needs to include code to induce pop-up windows in their software. Programs often run several DLLs at one time to go about all the processes that are needed.

Shadowpad takes advantage of DLL sideloading, which is when a legitimate DLL or program is executed and calls a spoofed DLL that loads Shadowpad. The attacker can place the malicious DLL in the first file location the legitimate executable will load, and then the malicious DLL will load. As DLL’s only work when called upon by another program, executing a simple, real executable like TosBtKbd.exe loads a DLL named tosbtkbd.dll that then loads the Shadowpad boot process.[5] This type of attack is hard to detect, as Windows sees a legitimate executable being run, often with similar names that go easily unnoticed. Shadowpad is also heavily encrypted and obfuscated, making it even harder to detect activity.[6]

Once on the system, the obfuscated shellcode de-compresses and decrypts, installs a root that establishes communication with the attacker’s C2 server, and begins to install plugins. All these processes are executed onto the system, then compressed and encrypted again to avoid detection, alongside moving files to locations not often used. The encryption key used in each attack is different, as it is generated based on the serial number of the victim’s C: serial number. The plugins that can be bought with Shadowpad are what truly makes Shadowpad so useful for attackers, and what gives the malware such a wide range of capabilities. Some of the most common plug-ins are a keylogger, Shell which enables an attacker to use Powershell on the victim’s machine, a Port map to map all open ports on the network and retrieve recent files from the victim’s library.[7] These functions can be removed remotely, further evading detection.

To communicate with the attacker’s C2 server, Shadowpad encrypts and compresses all information using QuickLZ and uses techniques like DNS tunneling, random domain generation, and HTTPS. QuickLZ is a common compression method, as it is one of the quickest and smallest file size methods available. This way, communication sends fewer, smaller packets back. DNS is a web protocol used to make browsing the internet easier, as it gives websites names like google.com, instead of needing to know the exact IP address of google.com. DNS is widely trusted and used, with firewalls letting DNS traffic pass through. Attackers can register a domain, and DNS will connect the victim’s machine to the attacker’s C2 server, enabling communication that is hard to track without investigating all packets on the network.[8]

Shadowpad also can use a Domain Generation Algorithim (DGA), randomly generating domains to communicate with the C2 servers, which not only makes communication even more hidden, but ensures the victim cannot blacklist a certain domain to stop the malware. The C2 and affected machine create the domain together, almost like a lock and a key. HTTPS is a commonly used protocol that is used to communicate with websites, as it encrypts traffic and ensures that the domain is valid, using certificates. Using google.com again, HTTPS first connects to google.com, then checks to see if a TLS certificate is present, showing the authenticity of the website. Then, an encryption key that google.com and your machine agree on is used and all packets are encrypted. For Shadowpad, HTTPS is used to ensure that communication to and from the C2 server cannot be intercepted. All three of these methods are hard to crack without extensive effort and technical knowledge, something lacking from many victims.

Shadowpad is designed to be a virtual stalker, lurking in the background on victim’s machines, stealing information. Shadowpad can also be upfront, executing commands on the machine to do what the attacker pleases. This malware is technically sound from installation to running processes, with code and communication both hidden well. The use of normal Windows processes to load the malware evades anti-virus software, and the ability to remove plugins remotely again offers attackers another avenue of obfuscation. Therefore, Shadowpad can be used for a wide range of cyber-attacks, both for espionage and personal financial gain.

Actors and Use Cases

Shadowpad is used by Chinese threat actor groups such as Fishmonger, APT41/Barium, and People’s Liberation Army (PLA) cyber groups like Tick and Tonto. APT41 and Fishmonger have both been linked to i-Soon, a software company that receives contracts from the Chinese Ministry of State Security (MSS) to conduct hacker-for-hire operations.[9] PLA cyber groups target neighboring Asian countries per their specific theater command’s objectives. For example, a PLA team working for the Chinese Northern Theater command may target South Korea to try to plant malware sitting idly by in case conflict arises. Shadowpad has been cited for using Hong Kong and Chinese-based C2 server locations, and the attacks are in line with Chinese objectives, along with Chinese characters have been found in Shadowpad code.[10] Along with the choice of specific victims, Shadowpad uses a custom algorithm that without the key is near useless, again showing the tight control of the malware.[11] Shadowpad has been used for many attacks against targets who do not fully align with China, such as an Asian-focused NGO and a Taiwanese governmental organization. This shows the malware is tightly controlled and is only available to be bought among Chinese groups for attacks that do not conflict with Chinese objectives.

One of the highest-profile attacks that utilized Shadowpad was the 2017 infiltration of Net Sarang. Net Sarang is a South Korean software company that develops server management software, and in mid-2017 APT41 managed to breach Net Sarang. They installed a backdoor in the nssock2.dll in five versions of Net Sarang software, meaning thousands of companies that used this software had Shadowpad lurking in their systems. Shadowpad would just ping the C2 servers with basic target info like IP and network configuration until a command was sent to activate. Once activated, attackers had a much better understanding of many companies’ network architecture. Infected software was available from June to August of 2017. [12]Affected companies were in the banking, energy, manufacturing, healthcare, and critical infrastructure fields. The attack was only noticed when Net Sarang noticed strange DNS requests, going to servers in Hong Kong. This attack shows that one breach of a supply chain can impact large swathes of the corporate world, and how dangerous this malware can be. Not only was Shadowpad installed on many systems, but data was stolen from critical fields that gave China technical know-how and blueprints, furthering Xi Jinping’s goal for China to be a world leader in manufacturing and high end equipment.

Between June and October of 2024, Shadowpad was utilized to target several European healthcare organizations. Attackers gained access through CVE-2024-24919, which enabled them to gain password hashes on Checkpoint Security Gateway devices with specific VPN configurations. [13] The attackers, who have not been identified beyond a Chinese threat actor group, then side-loaded logexts.dll from logger.exe to boot Shadowpad.[14] Shadowpad in this usage case was not used for espionage, it was used to deploy the NaiLaoLocker ransomware. Once Shadowpad was active, attackers loaded usysdiag.exe, a legitimate executable signed by a Beijing company, to sideload sensapi.dll which deployed usysdiag.exe.dat, loading NaiLaoLocker, a ransomware program, onto systems.[15] Then, data was encrypted using ES-256-CTR encryption, and files were renamed to have .locked after them, with a ransom note telling victims to contact a proton mail account and pay in Bitcoin to get their files back. As the attack used Shadowpad, it is apparent it was an incursion by a Chinese APT. More interestingly, cryptocurrency is outlawed in China, so attackers either used offshore wallets or had Chinese government backing. This attack is odd, as Shadowpad is primarily employed for espionage operations. It provides the possibility that the same hackers-for-hire that target governmental organizations may moonlight using similar techniques and software for personal profit.

In early-mid 2022, Fishmonger, a group associated with i-Soon, breached many targets using Shadowpad and other backdoors. The victims targeted by Shadowpad included a Taiwanese governmental organization, a US NGO primarily focusing on Asia, and a Thai governmental organization.[16] i-Soon has been confirmed to help hire and manage attacks for the MSS, proved by a published indictment by the US Department of Justice against members of Fishmonger. Powershell was used to install Shadowpad after a compromise of the victim’s web system. Log.dll was again abused to sideload Shadowpad, probably from a spoofed anti-virus software installed. Targeting an Asian-focused NGO fits with the Chinese goal of having regional dominance and targeting the Taiwanese government fits into the Chinese goal of re-unification with Taiwan. The information gained from these attacks could enable China to shut down the NGO’s operations, alongside planting long-term access into Taiwanese servers that could be activated during a potential attack on Taiwan. Targeting Thailand also makes sense, as the Thai government uses both the US and China, so gaining an understanding of Thai decision-making is crucial. Overall, the Fishmonger attack shows that Shadowpad is deployed to further Chinese goals.

History

Before Shadowpad, PlugX was the primary choice for Chinese attacks dating back to 2008. Unlike Shadowpad, PlugX was much less tightly controlled and has been used by a variety of actors, not just Chinese-backed APT groups. It has very similar functionality to Shadowpad, but more dated. PlugX does not have the modular plug-in capability of Shadowpad and is used in less sophisticated attacks owing to the easier detection.[17] PlugX uses the same DLL sideloading as Shadowpad. Sentinel One attributes both PlugX and Shadowpad to the same author, 无花果(WHG), a hacker with ties to APT41 and who has advertised his sale of software online.[18] Also, the controller file name for PlugX is SC, and for Shadowpad it is SC (1.1). Several of these Chinese APT groups are affiliated, as they break up or join new groups over the years. For example, APT41 has had members in Barium, Double Dragon, APT41, and Winnti Group among others. [19]

Shadowpad was first a major news headline with the 2017 Net Sarang attack and subsequently has frequently been used. Shadowpad has been known to target supply chains, pushing malware out to many customers to give attackers the most bang for their buck in breaches. As these attacks are sophisticated, acquiring and using the malware is expensive, so it is only used by advanced APT groups with access to funding.

Conclusion

Shadowpad is a modular malware used by Chinese threat actor groups since 2017 to discretely gain access to a Windows machine and perform many tasks depending on which plugins are active. The malware is advanced, employing many obfuscation methods and evolving with every attack. Shadowpad can lurk in a system once it has gained access, giving Chinese APT groups long-term access to a victim’s system. This can either be for data theft, a time-honored strategy employed by the Chinese government[20], or to plant offensive malware such as ransomware. Shadowpad uses many methods to gain access to a victim’s system, but the loading of the malware always hijacks DLL loading to sideload the payload. This malware was chosen due to its ability to perform many functions and evade detection owing to the plug-in and “plug-out” control available to the attacker.

References

Altamura, John M. “Chinese Malware Historical Perspective,” 2020. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2476123966?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true&sourcetype=Dissertations%20&%20Theses.

Bracken, Becky. “Chinese Hacker Group Tracked Back to ISoon APT Operation.” DarkReading, 2025. https://www.darkreading.com/cyberattacks-data-breaches/chinese-espionage-hacker-group-isoon-apt-operation.

Ćemanović, Amar. “NailaoLocker Ransomware Uses VPN Flaw to Attack Healthcare Orgs.Pdf,” Winter 25, 2AD. https://cyberinsider.com/nailaolocker-ransomware-uses-vpn-flaw-to-attack-healthcare-orgs/.

“Dynamic-Link Library.” Maldev Academy, Autumn 4AD. https://maldevacademy.com/modules/9?all_modules=1&view=blocks.

Faou, Matthieu. “Operation FishMedley Targeting Governments, NGOs, and Think Tanks.” Welivesecurity, 2025. https://www.welivesecurity.com/en/eset-research/operation-fishmedley/.

Haruyama, Takahiro. “VB2022-Tracking-the-Entire-Iceberg.” VMware, 2022. https://www.virusbulletin.com/uploads/pdf/conference/vb2022/slides/VB2022-Tracking-the-entire-iceberg.pdf.

Hsieh, Yi-Jhen, and Joey Che. “Shadowpad – a Masterpiece of Privately Sold Malware In Chinese Espionage,” 2021. https://assets.sentinelone.com/c/Shadowpad?x=P42eqA.

Lunghi, Daniel. “Updated Shadowpad Malware Leads to Ransomware Deployment _ Trend Micro (FR).Pdf,” Winter 25, 2AD. https://www.trendmicro.com/fr_fr/research/25/b/updated-shadowpad-malware-leads-to-ransomware-deployment.html.

Pichon, Marine, and Alexis Bonnefoi. “Meet NailaoLocker_ a Ransomware Distributed in Europe by ShadowPad and PlugX Backdoors.Pdf,” Summer 25, 2AD. https://www.orangecyberdefense.com/global/blog/cert-news/meet-nailaolocker-a-ransomware-distributed-in-europe-by-shadowpad-and-plugx-backdoors.

PTSecurity. “Shadowpad: New Activity from the Winnti Group.Pdf,” 2020. https://pt-corp.storage.yandexcloud.net/upload/corporate/ww-en/pt-esc/winnti-2020-eng.pdf.

Rapid7. “CVE-2024-24919.” Checkpoint Security Gateway, 2024. https://www.rapid7.com/blog/post/2024/05/30/etr-cve-2024-24919-check-point-security-gateway-information-disclosure/.

Securelist. “ShadowPad in Corporate Networks.” Securelist, 2017. https://securelist.com/shadowpad-in-corporate-networks/81432/.

Team, Counter Threat Unit Research. “ShadowPad Malware Analysis _ Secureworks.Pdf.” Secureworks, 2022. https://www.secureworks.com/research/shadowpad-malware-analysis.

Team, Cybereason Global SOC. “Threat Analysis Report- PlugX RAT Loader Evolution.Pdf.” Cybereason, n.d. https://www.cybereason.com/blog/threat-analysis-report-plugx-rat-loader-evolution.

Team, Dr. Web Threat Analysis. “BackDoor.ShadowPad.1.” Dr. Web Malware Description Library, 2020. https://vms.drweb.com/virus/?i=21995048.

Team, Palo Alto Threat Detection. “What Is DNS Tunneling.” Palo Alto Networks, n.d. https://www.paloaltonetworks.com/cyberpedia/what-is-dns-tunneling.

“The Origins of APT 41 and ShadowPad Lineage.” Cyfirma, 2022. https://www.cyfirma.com/research/the-origins-of-apt-41-and-shadowpad-lineage/.

[1] Counter Threat Unit Research Team, “ShadowPad Malware Analysis _ Secureworks.Pdf,” Secureworks, 2022, https://www.secureworks.com/research/shadowpad-malware-analysis.

[2] Takahiro Haruyama, “VB2022-Tracking-the-Entire-Iceberg,” VMware, 2022, https://www.virusbulletin.com/uploads/pdf/conference/vb2022/slides/VB2022-Tracking-the-entire-iceberg.pdf.

[3] Daniel Lunghi, “Updated Shadowpad Malware Leads to Ransomware Deployment _ Trend Micro (FR).Pdf,” Winter 25, 2AD, https://www.trendmicro.com/fr_fr/research/25/b/updated-shadowpad-malware-leads-to-ransomware-deployment.html.

[4] “Dynamic-Link Library,” Maldev Academy, Autumn 4AD, https://maldevacademy.com/modules/9?all_modules=1&view=blocks.

[5] Team, “ShadowPad Malware Analysis _ Secureworks.Pdf.”

[6] Dr. Web Threat Analysis Team, “BackDoor.ShadowPad.1,” Dr. Web Malware Description Library, 2020, https://vms.drweb.com/virus/?i=21995048.

[7] Yi-Jhen Hsieh and Joey Che, “Shadowpad – a Masterpiece of Privately Sold Malware In Chinese Espionage,” 2021, https://assets.sentinelone.com/c/Shadowpad?x=P42eqA.

[8] Palo Alto Threat Detection Team, “What Is DNS Tunneling,” Palo Alto Networks, n.d., https://www.paloaltonetworks.com/cyberpedia/what-is-dns-tunneling.

[9] Becky Bracken, “Chinese Hacker Group Tracked Back to ISoon APT Operation,” DarkReading, 2025, https://www.darkreading.com/cyberattacks-data-breaches/chinese-espionage-hacker-group-isoon-apt-operation.

[10] PTSecurity, “Shadowpad: New Activity from the Winnti Group.Pdf,” 2020, https://pt-corp.storage.yandexcloud.net/upload/corporate/ww-en/pt-esc/winnti-2020-eng.pdf.

[11] “The Origins of APT 41 and ShadowPad Lineage,” Cyfirma, 2022, https://www.cyfirma.com/research/the-origins-of-apt-41-and-shadowpad-lineage/.

[12] Securelist, “ShadowPad in Corporate Networks,” Securelist, 2017, https://securelist.com/shadowpad-in-corporate-networks/81432/.

[13] Rapid7, “CVE-2024-24919,” Checkpoint Security Gateway, 2024, https://www.rapid7.com/blog/post/2024/05/30/etr-cve-2024-24919-check-point-security-gateway-information-disclosure/.

[14] Marine Pichon and Alexis Bonnefoi, “Meet NailaoLocker_ a Ransomware Distributed in Europe by ShadowPad and PlugX Backdoors.Pdf,” Summer 25, 2AD, https://www.orangecyberdefense.com/global/blog/cert-news/meet-nailaolocker-a-ransomware-distributed-in-europe-by-shadowpad-and-plugx-backdoors.

[15] Amar Ćemanović, “NailaoLocker Ransomware Uses VPN Flaw to Attack Healthcare Orgs.Pdf,” Winter 25, 2AD, https://cyberinsider.com/nailaolocker-ransomware-uses-vpn-flaw-to-attack-healthcare-orgs/.

[16] Matthieu Faou, “Operation FishMedley Targeting Governments, NGOs, and Think Tanks,” Welivesecurity, 2025, https://www.welivesecurity.com/en/eset-research/operation-fishmedley/.

[17] Cybereason Global SOC Team, “Threat Analysis Report- PlugX RAT Loader Evolution.Pdf,” Cybereason, n.d., https://www.cybereason.com/blog/threat-analysis-report-plugx-rat-loader-evolution.

[18] Hsieh and Che, “Shadowpad – a Masterpiece of Privately Sold Malware In Chinese Espionage.”

[19] John M. Altamura, “Chinese Malware Historical Perspective,” 2020, https://www.proquest.com/docview/2476123966?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true&sourcetype=Dissertations%20&%20Theses.

[20] Altamura, “Chinese Malware Historical Perspective.”