By Sutton Marks and Yancey Wegner

Introduction

On the topic human rights there have been numerous political protests in the country of Iran. Such protests have led to civil unrest and loss of lives, examples including Bloody November and the death of Mahsa (Jini) Amini in police custody. While citizens attempt justice against their oppressors, internet censorship and shutdowns have limited their capability to do so. With their options limited, some citizens may turn to privacy enhancing technologies. Therefore, utilizing publicly available Tor metrics and network interference data we argue that there is a correlation between political repression in Iran and increases in dark web activity.

Background

The Islamic Republic of Iran, led by Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, is an authoritarian state which suppresses dissent, controls the media, and severely restricts access to and communication of information that it views as a threat. With the current leader in power since 1989, Iran has undergone little political change, and popular uprisings demanding reform are often met with violence and mass arrests. The regime maintains its power and authority by undermining its citizens’ ability to speak openly and assemble and by controlling the media. According to Reporters without Borders, Iran currently ranks 176th in press freedom out of 180 countries, reflecting the extent to which they suppress alternative viewpoints and avoid accountability.[1]

The Iranian regime has a long history of intense political repression, brutally silencing those who oppose the country’s leadership and policies. One of the most prominent examples of political suppression in Iran came in 2005, when student protestors in Mahabad, Iran, were demonstrating in commemoration of a previous student protest. A leading activist in the protest, Shawaneh Ghaderi, was shot by Iranian law enforcement, tied to a car, and driven across the streets of Tehran until his death.[2] Later, the 2009 presidential election and widespread accusations of electoral fraud led to massive protests throughout Iran.[3] The protests, many with the slogan “Death to the Dictator”, were met with violence, executions, and mass arrests. Neda Agha-Soltan, a 26-year-old unarmed protestor, was shot and killed in Tehran, just one example of the many deaths perpetrated by Iranian forces during the protests. In addition to the murders on the street, over 4,000 people were arrested and at least 115 prisoners were executed.[4] The Green Movement, as it came to be known, presented an unfamiliar and unparalleled threat to the stability of Iranian regime.[5] Unlike previous protests which were orchestrated through in-person meetings, the Green Movement was the first to see the large-scale coordination over the Internet. At the time, Twitter was exploding in popularity, and Iranian citizens could learn in real-time where protests would occur and how their government was responding. Twitter enabled mass assembly at a magnitude never seen in Iran and gave people a platform for dissent.[6]

In large part due to the Green Movement, Iran perceives an open Internet as a threat to its grip on power, as it would provide a forum for dissent and invite Western ideas into Iran. Through Internet censorship, Iran aims to prevent a “soft revolution” in which citizens adopt pro-democracy and pro-reform positions through the Internet, compromising Iran’s stability.[7] To maximize its control over its citizens’ online activities, Iran established an organization known as the Supreme Council of Cyberspace, which develops censorship policies and other methods of controlling cyberspace. Those strategies include the so-called National Information Network; a proposed Iranian Internet separated from the rest of the world. Requiring that all devices connect to NIN would grant Iran the ultimate censorship capabilities, as traditional circumvention methods would be ineffective. In addition to the SCC, Iran has a cyber police force known as FATA which is responsible for identifying dissidents online and apprehending them. Due to the efforts by the SCC and FATA to restrict Internet freedoms, punish online dissent, and control what can be viewed online, Iran is often referred to as a digital authoritarian state.[8]

Despite Iran’s elaborate efforts to control and censor its Internet, anonymity-granting technologies like the Tor network provide a consistent means for censorship evasion and online dissent. While Iran may implement IP-based blocks on directory-listed Tor nodes, bridges and pluggable transports provide more secure and resilient methods for the heavily censored to connect.[9] The use of pluggable transports makes detecting censorship evasion very difficult, allowing many people in heavily censored countries to continue accessing the dark web. One such pluggable transport, Snowflake, uses lightweight proxies to establish connections to the Tor network using the WebRTC specification. At the height of the 2022 protests in Iran, Iranians accounted for 67% of all Tor users connecting over Snowflake.[10] Snowflake is especially effective at evading the deep packet inspection commonly used by repressive regimes to identify bridge connections. It does so by disguising traffic as if the user were accessing popular sites like Google and Skype.[11] While more susceptible to detection when not using pluggable transports, bridges remain a popular way of accessing the Tor network in Iran. According to Tor Metrics, Iran had the second highest number of bridge users in the past 5 years at 16.47% percent of total traffic, with 17710 average daily users.[12]

According to a researcher at the Centre for International Governance Innovation, political repression appears to be correlated with an increased use in dark web technologies. The heightened use of Tor, the author believes, is driven by a need to express basic political rights when other means to do so are monitored and suppressed.[13] This essay will explore that hypothesis through the perspective of Iran, examining recent acts of political repression by the regime and correlated increases in dark web activity.

Case Study I – Bloody November

In 2019, Iran was suffering economically due to US sanctions and sought to increase its domestic revenue to rectify its economic hardships. In pursuit of that goal, the Iranian government announced in November of that year that it would ration fuel and raise its price by 50 to 200 percent.[14] The announcement immediately set off mass protests throughout the country, known as Bloody November, with hundreds of thousands of people taking to the streets in rebellion. Not only were people upset about the drastic increase in fuel costs, but they were also widely dissatisfied with the regime. Within a few days, the protests had grown to many cities throughout Iran, with some protesters advocating for the end of the current Iranian regime and the installation of new leadership. What began as outrage over fuel costs erupted into the most violent popular uprising in Iran since the Islamic Revolution of 1979.[15]

To maintain their firm grip on power, the government of Iran began a ruthless crackdown against the protestors, brutally murdering many and arresting countless more. During the Mahshahr Massacre, for instance, members of the IRGC shot and killed protestors using heavy machine guns and helicopters, while allegedly killing some innocent civilians not participating in the protests.[16] Amnesty International believes close to 400 people were killed during the national protests, while Reuters places the death toll at 1,500.[17] Those deaths primarily occurred over the four days of the original protests, demonstrating how quickly and mercilessly the government responded to the uprising. In addition to physically suppressing the protests, Iran also took unprecedented steps to censor its citizens by instituting a week-long Internet blackout.[18] During that time, most citizens could not access the Internet outside of government sites and banks, with Internet connectivity only seven percent of its typical levels.[19] By restricting Internet access, Iran was not only able to limit the organization of protests online, but it was also able to hide the true magnitude of the uprising and how viciously they had suppressed it. Furthermore, shutting down Internet access allowed Iran to temporarily stop all access to the dark web. While advanced censorship evasion techniques exist for the dark web that enable its continued operation, not being able to reach other devices on the Tor network renders it nonfunctional. In addition to shutting down the Internet, the Supreme National Security Council of Iran ordered that all media outlets refrain from reporting on the ongoing protests.[20]

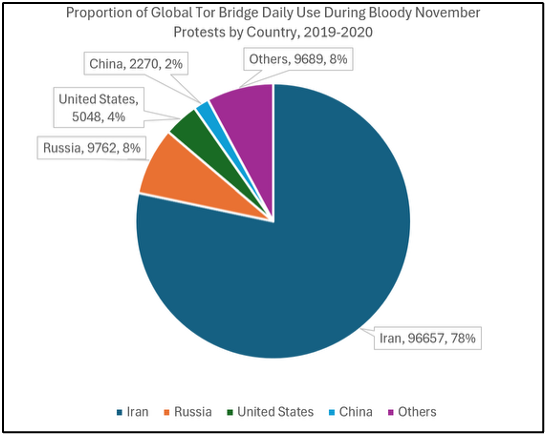

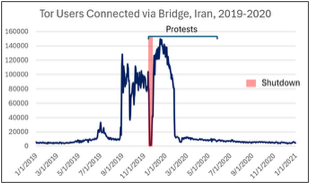

During the early period of the protests, as well after the shutdown had concluded, the Tor network experienced a surge in traffic from Iran. While traditional news and social media websites are monitored heavily by Iran as discussed above, the Tor network enabled citizens to evade such surveillance and censorship in many cases and access discussion forums and other dark web media sources. The number of users accessing the Tor network via bridges was at an all-time high after the Internet shutdown ended and continued throughout the smaller-scale protests that followed the original, four-day incident.[21] From the start of the protests on November 15, 2019, until the following February, Iran had the most users accessing Tor via bridges of any country in the world. As shown in the Figure 1, Iran’s traffic constituted 68.09% of global bridge use during that time, with 96657 mean daily users.[22]

Figure 1

Proportion of Global Tor Bridge Use During Bloody November Protests by Country, 2019-2020

While there was relatively high use of Tor bridges prior to the Bloody November protests, the usage increased significantly immediately after the Internet shutdown ended a few days into the protests. Daily bridge use in Iran reached a peak of 150,135 users on December 17, 2019, amid the smaller yet widespread protests that followed the original uprising. By March of 2020, the number of users connecting to the Tor network via bridges had fallen significantly, corresponding to a meaningful decline in protest intensity.[23] The COVID-19 pandemic began at the height of Tor activity in Iran and may have been responsible for the sudden decline in dark web activity and protests in the country.

Figure 2

Tor Users Connected Via Bridge in Iran, 2019-2020

While there are some exceptions, such as elevated use of the Tor network in the early fall of 2019, the number of bridge-connecting users during Bloody November was highly anomalous. Unlike previous upticks in Tor usage in Iran, the Bloody November protests saw consistent Tor bridge activity sustained at high levels for over two months. The peak in the data coupled with the increase in Tor use as the protests intensified and the decrease as they ended suggests that the bridge use was directly correlated with the protests. Organizing, discussing, and attending the Bloody November protests appears to be associated with increased Tor activity. This supports the conclusion of prior research that the attempts at political expression in highly repressive regimes often correspond with increases in dark web use.[24]

Case Study II – Protests After the Death of Mahsa (Jini) Amini

On September 13, 2022, Mahsa (Jina) Amini, a twenty-two-year-old was detained in Tehran by the Guidance Patrol (Gasht-e-Ershad) for allegedly wearing her hijab incorrectly.[25] Three days following her arrest, Mahsa Amini was in a coma and died on September 16, 2022.[26] While the government claims that her death was caused by a medical condition, Iranian citizens strictly deny this believing she was murdered. Reports on the supposed murder have varied, therefore details will not be included. Amnesty International has, however, called the arrest “arbitrary”.[27]

The protest first began in her home of Saqez, the capital of the Iranian province of Kurdistan. However, protest would spread to all over parts of Iran, often by young high school and college aged women. Protesters included those seeking justice for what had happened to Amini, but others sought the end of the regime and ongoing oppression of women, with chants like “Down with the Islamic Republic”. Actions taken included women holding pictures of Amini, removal of hijabs, and cutting one’s hair.[28] Social media would ignite these protests to spread across Iran. On September 19, a feminist group called for a protest on Keshavarz Boulevard by the University of Tehran. One to two thousand people attended and began to chant the Kurdish revolutionary slogan, “Woman, Life, Freedom”. As Amini was a part of the 10% Kurdish population in Iran. Spearheaded by most young women at the front lines of protest, it spread to 120 cities with people blocking intersections to remove headscarves and burn them. Demonstrations also occurred in High Schools and Universities despite police and paramilitary forces.[29] On September 30, protests in Zahedan, Sistan, and Baluchistan provinces in Southern Iran were shut down. At least forty-one people were killed, with Iranian human rights groups terming the incident “Bloody Thursday”.[30] By mid-November crackdown by the state increased and became more violent. Particularly in areas with a heavy Kurdish community, repression was brutal. By the end of December, 500 demonstrators were killed, including sixty-seven children and 15,000 people arrested, indicting at least twenty-six people with “waging war against God”, a crime with the death penalty. It was also at this time that the movement had lost momentum due to the arrests of students and expulsion, suspension, or banning of large student bodies on campuses.[31]

While the movement was significant as a feminist movement, it also showed a type of protesting different from that of the Green Revolution or Bloody November. Such difference was the various demographics that had participated in solidarity with one another. As Amini was Kurdish and Sunni, the movement was also viewed as a fight against Kurdish discrimination and mistreatment of Sunni people by the Shi’ite regime.[32] The Baluch community also found a place within the movement.[33] Wealthier individuals and men also participated, however the participation by men has been controversial due to patriarchal and misogynistic rhetoric used and some men rationalizing their participation as protecting their own honor by protecting the honor of Women (their property).[34] Additionally, the Coordinating Council of Teachers’ Association called for 3-day period of public mourning for the student killed in protests, lawyers protested police repression in their association’s buildings, and doctors assembled outside the Iran Medical Council to protest police raids on hospitals to arrect injured protesters.[35]

While this movement had occurred, the regime went through great lengths to stiffen its momentum on social media. Such included restricted internet access on September 21 when graphic protests images appeared on social media.[36] To support this fact is The Open Observatory of Network Interference report that for 13 consecutive day following September 21, 2022, to October 3, 2022, the Iranian government had implemented a “digital curfew”, shutting down access to mobile networks from 4:00PM local time until midnight. The network providers affected include Irancell, Rightel, and MCCI.[37] Such data was collected by the Internet Outage Detection and Analysis (IODA) and presented by OONI. Furthermore, the shutdown targeted social media platforms like Instagram or WhatsApp to obstruct information protesters and Iranians with the rest of the world.[38]

The Iranian government has also produced disinformation campaigns that insisted that the United States, with joint efforts of the “Zionist regime”, was the cause of Amini’s death. In fact, Supreme Leader Khamenei used this argument as his initial response to the protest, mentioning “America” 11 times and “enemy” 9 times in a single speech. This attempt to label America as the actual cause of Amini’s death failed, and the slogan “Our enemy is right here; they [the regime] lie that it is America” persisted.[39] The regime then tried to spread the narrative that there was no better alternative to their rule, as opposition groups are incapable of presenting a better alternative or ensuring a better future. State affiliated media and pro-regime accounts on social media also promoted the “soft war” by conducting ‘psychological operations’, as Secretary General of the Islamic Revolutionary Front in Cyberspace – Rouhollah Momen-Nasab called it, to discredit opposition. Example included targeting celebrities like footballer Ali Karimi and actresses Afsaneh Baygan and Azadeh Samadi, all of whom vocally supported the movement. The accounts claimed that Karimi had sold his Instagram and X accounts to Israeli intelligence services, and that Baygan and Samadi, for taking off their hijabs, were mentally ill and were forced to undergo weekly psychological treatments.[40]

To stiffen journalists in support of the movement, many were arrested. Examples include Niloofar Hamedi who published evidence of Amini in the hospital. Reporters without borders indicated that seventy-nine journalists had been arrested since the death of Mahsa (Jina) Amini, twenty-four of whom has been sentenced to six months and six years in prison for “anti-state propaganda” and other charges. Particular attention has been given to female journalist reporting on the movement, as thirty-one of the seventy-nine were women. What gives power to the government is keeping the rules dictating what can and cannot be said in the media arbitrary, so that any reason is one to arrest.[41]

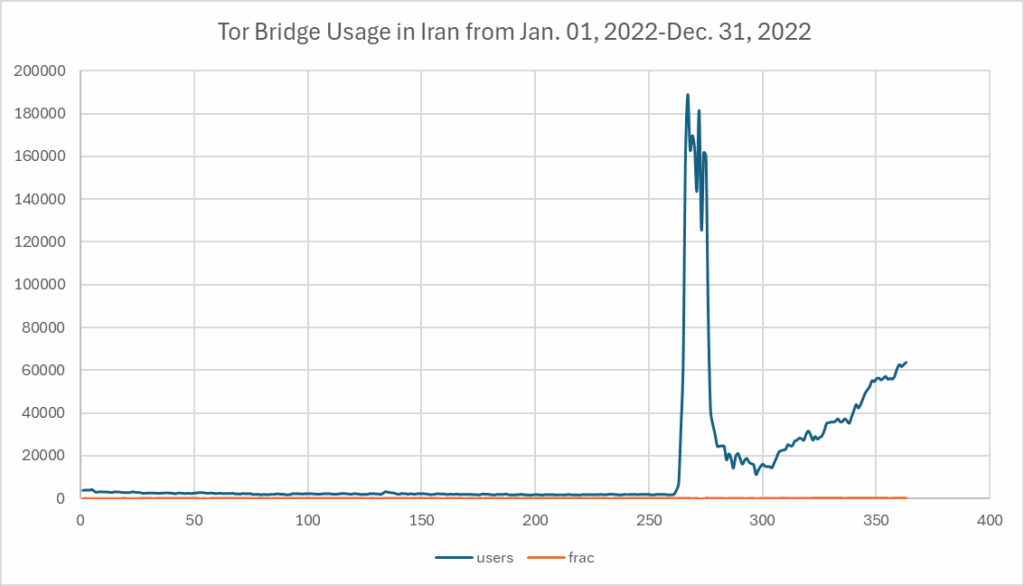

Using this as our basis, we argue that this increase in censorship and political unrest leads to an increase in dark web usage. Presumably for the use of getting information out to the public anonymously and bypassing surveillance by the government. To support this inference, we collected Tor metric data from the Tor Metrics website. Particularly focusing on bridge usage in Iran. Figure 3 below shows data collected.

Figure 3

Tor Bridge Usage in Iran from January 1, 2022 – December 31, 2022

The blue line represents users on the Tor network, while the orange line represents the fraction of them utilizing a Tor bridge. Identifying the timeline on the graph, we can observe a commonality between the timeline of the political movement triggered by Mahsa (Jini) Amini’s death and Tor Bridge usage. As previously stated, the movement began September 16, 2022, and increased into October. However, as suppression continued and brutally increased, the protest lost momentum by December. Evidentially, we see that a see that similar decrease in December on the graph. Therefore, we can argue a correlation between the Mahsa (Jini) Amini political movement and Tor Bridge usage. This is not certain, however, and no causal relation is made. In relation to our argument, it helps supports the idea that political repression in Iran can lead to an increase in Dark Web activity.

Conclusion

The objective of this blog post was to identify a correlation between political repression and increases in dark web activity. Utilizing publicly available metrics we aligned political events, particularly Bloody November and the Death of Mahsa (Jini) Amini, in Iran with noticeable fluctuations in Iranian use of Tor bridges and network behavior. While we do not find a causation between the political repression in Iran, we believe there is suitable evidence to justify our argument. Going forward, more substantial evidence will be necessary.

References

Akbarzadeh, S., Naeni, A., Bashirov, G., & Yilmaz, I. (2024). The web of Big Lies:

state-sponsored disinformation in Iran. Contemporary Politics, 31(2), 328–

347. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569775.2024.2374593

Akbarzadeh, S., Naeni, A., Yilmaz, I., & Bashirov, G. (2024). Cyber Surveillance and Digital Authoritarianism in Iran. https://www.globalpolicyjournal.com/sites/default/files/pdf/Akbarzadeh%20et%20al.%20-%20Cyber%20Surveillance%20and%20Digital%20Authoritarianism%20in%20Iran.pdf

Alsabah, M., & Goldberg, I. (2016). Performance and Security Improvements for Tor. ACM Computing Surveys, 49(2), 1–36. https://doi.org/10.1145/2946802

Bocovich, C., Breault, A., Fifield, D., Wang, X., & Wang, S. (2024). Snowflake, a censorship circumvention system using temporary WebRTC proxies. https://www.usenix.org/system/files/usenixsecurity24-bocovich.pdf

Golkar, S. (2011). Liberation or Suppression Technologies? The Internet, the Green Movement and the Regime in Iran. Australian Journal of Emerging Technologies and Society, 9(1). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/264845409_Liberation_or_Suppression_Technologies_The_Internet_the_Green_Movement_and_the_Regime_in_Iran_Liberation_or_Suppression_Technologies_The_Internet_the_Green_Movement_and_the_Regime_in_Iran

Iran Fact Records. (2022). Bloody November: The Travesty of Propaganda and Impunity of Human Tragedy. https://iranfactrecords.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/aban1398_iranfactrecords.pdf

Iran Freedom. (2020, October 31). In Memory of Mahshahr Massacre Victims of 2019 Iran Protests – Iran Freedom. Iran Freedom. https://iranfreedom.org/en/articles/2020/10/in-memory-of-mahshahr-massacre-victims-of-2019-iran-protests/19428/

Iran International. (2022, November 13). Iranians Plan Three-Day Protests To Mark “Bloody November.” Iran International. https://www.iranintl.com/en/202211138108

Jardine, E. (2016). Tor, what is it good for? Political repression and the use of online anonymity-granting technologies. New Media & Society, 20(2), 435–452. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444816639976

Khatam, A. (2023). Mahsa Amini’s killing, state violence, and moral policing in Iran. Human Geography, 16(3), 299-306. https://doi.org/10.1177/19427786231159357 (Original work published 2023)

Kirk, A. (2010). Political Repression and Islam in Iran. Digital Commons. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/hrhw/vol10/iss1/23

NetBlocks. (2019, November 15). Internet disrupted in Iran amid fuel protests in multiple cities. NetBlocks. https://netblocks.org/reports/internet-disrupted-in-iran-amid-fuel-protests-in-multiple-cities-pA25L18b

Open Observatory of Network Interference. (2022, 11 29). Technical multi-stakeholder report on Internet shutdowns: The case of Iran amid autumn 2022 protests. Retrieved from OONI.org: https://ooni.org/post/2022-iran-technical-multistakeholder-report/#mobile-network-outages

Parsa, M. (2020). Authoritarian Survival: Iran’s Republic of Repression. Journal of Democracy, 31(3), 54–68. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2020.0045

Quintin, C. (2022, October 4). Snowflake Makes It Easy For Anyone to Fight Censorship. Electronic Frontier Foundation. https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2022/10/snowflake-makes-it-easy-anyone-fight-censorship?language=en

Rabiei, K. (2020). Protest and Regime Change: Different Experiences of the Arab Uprisings and the 2009 Iranian Presidential Election Protests. International Studies, 57(2), 144–170. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020881720913413

Radeck, M., & Khodakarim, A. (2022). Iran: the beginning of feminist revolution. Horizon Insights, 1.

https://behorizon.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Horizon-Insights_2022_4.pdf#page=5

Reporters Without Borders. (2025). Iran. Rsf.org. https://rsf.org/en/country/iran

Safi, M. (2019, November 21). Iran’s digital shutdown: other regimes “will be watching closely.” The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/nov/21/irans-digital-shutdown-other-regimes-will-be-watching-closely

Shahi, A., & Abdoh-Tabrizi, E. (2020). Iran’s 2019–2020 Demonstrations: The Changing Dynamics of Political Protests in Iran. Asian Affairs, 51(1), 1–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/03068374.2020.1712889

Shahrokni, N. (2022). In Her Name:(Re) Imagining feminist solidarities in the aftermath of the Iran protests. Feminist Studies, 48(3), 896-901. https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/434/article/884106/summary?casa_token=k_OfHEcwwgQAAAAA:fCLgnztVoUAXh1S1BXn_7wfooeXfltJKwDb_rZ-OZ3ld36uIs9jEcBJPqDMVFuG8GNjEHYPIYexZ

Siboni, G., & Kronenfeld, S. (2012). Iran and Cyberspace Warfare. Strategic Affairs |, 4(3). https://www.inss.org.il/wp-content/uploads/systemfiles/MASA4-3Engd_Siboni%20and%20Kronenfeld.pdf

Tofangsazi, B. (2019). From the Islamic Republic to the Green Movement: Social Movements in Contemporary Iran. Sociology Compass, 14(1). https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12746

Tor Project. (n.d.-a). Bridge Users by Country. Tor Metrics. https://metrics.torproject.org/userstats-bridge-country.html

Tor Project. (n.d.-b). Top 10 Countries by Bridge Users. Tor Metrics. https://metrics.torproject.org/userstats-bridge-table.html

Uygur, H. (2022). Iran in the wake of Mahsa Amini’s death. Insight Turkey, 24(4), 11-22. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48706285?seq=1

[1] Reporters Without Borders. (2025). Iran. Rsf.org. https://rsf.org/en/country/iran

[2]Amy Kirk, “Political Repression and Islam in Iran,” Digital Commons, 2010, https://digitalcommons.du.edu/hrhw/vol10/iss1/23.

[3] Saeid Golkar, “Liberation or Suppression Technologies? The Internet, the Green Movement and the Regime in Iran,” Australian Journal of Emerging Technologies and Society 9, no. 1 (January 1, 2011), https://www.researchgate.net/publication/264845409_Liberation_or_Suppression_Technologies_The_Internet_the_Green_Movement_and_the_Regime_in_Iran_Liberation_or_Suppression_Technologies_The_Internet_the_Green_Movement_and_the_Regime_in_Iran.

[4]Misagh Parsa, “Authoritarian Survival: Iran’s Republic of Repression,” Journal of Democracy 31, no. 3 (2020): 54–68, https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2020.0045.

[5]Kamran Rabiei, “Protest and Regime Change: Different Experiences of the Arab Uprisings and the 2009 Iranian Presidential Election Protests,” International Studies 57, no. 2 (April 2020): 144–70, https://doi.org/10.1177/0020881720913413.

[6]Bashir Tofangsazi, “From the Islamic Republic to the Green Movement: Social Movements in Contemporary Iran,” Sociology Compass 14, no. 1 (December 17, 2019), https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12746.

[7]Gabi Siboni and Sami Kronenfeld, “Iran and Cyberspace Warfare,” Strategic Affairs | 4, no. 3 (2012), https://www.inss.org.il/wp-content/uploads/systemfiles/MASA4-3Engd_Siboni%20and%20Kronenfeld.pdf.

[8]Shahram Akbarzadeh et al., “Cyber Surveillance and Digital Authoritarianism in Iran,” March 2024, https://www.globalpolicyjournal.com/sites/default/files/pdf/Akbarzadeh%20et%20al.%20-%20Cyber%20Surveillance%20and%20Digital%20Authoritarianism%20in%20Iran.pdf.

[9]Mashael Alsabah and Ian Goldberg, “Performance and Security Improvements for Tor,” ACM Computing Surveys 49, no. 2 (September 21, 2016): 1–36, https://doi.org/10.1145/2946802.

[10]Cecylia Bocovich et al., “Snowflake, a Censorship Circumvention System Using Temporary WebRTC Proxies,” 2024, https://www.usenix.org/system/files/usenixsecurity24-bocovich.pdf.

[11]Cooper Quintin, “Snowflake Makes It Easy for Anyone to Fight Censorship,” Electronic Frontier Foundation, October 4, 2022, https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2022/10/snowflake-makes-it-easy-anyone-fight-censorship?language=en.

[12]Tor Project, “Top 10 Countries by Bridge Users,” Tor Metrics, n.d., https://metrics.torproject.org/userstats-bridge-table.html.

[13]Eric Jardine, “Tor, What Is It Good For? Political Repression and the Use of Online Anonymity-Granting Technologies,” New Media & Society 20, no. 2 (March 31, 2016): 435–52, https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444816639976.

[14]Iran International, “Iranians Plan Three-Day Protests to Mark ‘Bloody November,’” Iran International, November 13, 2022, https://www.iranintl.com/en/202211138108.

[15]Afshin Shahi and Ehsan Abdoh-Tabrizi, “Iran’s 2019–2020 Demonstrations: The Changing Dynamics of Political Protests in Iran,” Asian Affairs 51, no. 1 (February 14, 2020): 1–41, https://doi.org/10.1080/03068374.2020.1712889.

[16]Iran Freedom, “In Memory of Mahshahr Massacre Victims of 2019 Iran Protests – Iran Freedom,” Iran Freedom, October 31, 2020, https://iranfreedom.org/en/articles/2020/10/in-memory-of-mahshahr-massacre-victims-of-2019-iran-protests/19428/.

[17]Shahi and Abdoh-Tabrizi, “Iran’s 2019-2020 Demonstrations”

[18]Michael Safi, “Iran’s Digital Shutdown: Other Regimes ‘Will Be Watching Closely,’” The Guardian, November 21, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/nov/21/irans-digital-shutdown-other-regimes-will-be-watching-closely.

[19]NetBlocks, “Internet Disrupted in Iran amid Fuel Protests in Multiple Cities,” NetBlocks, November 15, 2019, https://netblocks.org/reports/internet-disrupted-in-iran-amid-fuel-protests-in-multiple-cities-pA25L18b.

[20]Iran Fact Records, “Bloody November: The Travesty of Propaganda and Impunity of Human Tragedy,” 2022, https://iranfactrecords.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/aban1398_iranfactrecords.pdf.

[21]Tor Project, “Bridge Users by Country,” Tor Metrics, n.d., https://metrics.torproject.org/userstats-bridge-country.html.

[22]Tor Project, “Top 10 Countries by Bridge Users,” Tor Metrics, n.d., https://metrics.torproject.org/userstats-bridge-table.html.

[23] Tor Project, “Bridge Users by Country.”

[24]Jardine, “Tor, What Is It Good For?

[25] Radeck, M., & Khodakarim, A. (2022). Iran: the beginning of feminist revolution.

Horizon Insights, 1.

https://behorizon.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Horizon- Insights_2022_4.pdf#page=5

[26] Uygur, H. (2022). Iran in the wake of Mahsa Amini’s death. Insight Turkey, 24(4),

11-22. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48706285?seq=1

[27] Radeck, M., & Khodakarim, A. (2022). Iran: the beginning of feminist revolution.

Horizon Insights, 1.

https://behorizon.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Horizon-Insights_2022_4.pdf#page=5

[28] Radeck, M., & Khodakarim, A. (2022). Iran: the beginning of feminist revolution.

Horizon Insights, 1.

https://behorizon.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Horizon-Insights_2022_4.pdf#page=5

[29] Radeck, M., & Khodakarim, A. (2022). Iran: the beginning of feminist revolution.

Horizon Insights, 1.

https://behorizon.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Horizon-Insights_2022_4.pdf#page=5

[30] Radeck, M., & Khodakarim, A. (2022). Iran: the beginning of feminist

revolution. Horizon Insights, 1.

https://behorizon.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Horizon-Insights_2022_4.pdf#page=5

[31] Khatam, A. (2023). Mahsa Amini’s killing, state violence, and moral policing in

Iran. Human

Geography, 16(3), 299-306. https://doi.org/10.1177/19427786231159357 (Original work published 2023)

[32] Radeck, M., & Khodakarim, A. (2022). Iran: the beginning of feminist

revolution. Horizon Insights, 1.

https://behorizon.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Horizon-Insights_2022_4.pdf#page=5

[33] Radeck, M., & Khodakarim, A. (2022). Iran: the beginning of feminist

revolution. Horizon Insights, 1.

[34] Shahrokni, N. (2022). In Her Name:(Re) Imagining feminist solidarities in the

aftermath of the

Iran protests. Feminist Studies, 48(3), 896-901. https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/434/article/884106/summary?casa_token=k_OfHEcwwgQAAAAA:fCLgnztVoUAXh1S1BXn_7wfooeXfltJKwDb_rZ-OZ3ld36uIs9jEcBJPqDMVFuG8GNjEHYPIYexZ

[35] Khatam, A. (2023). Mahsa Amini’s killing, state violence, and moral policing in

Iran. Human Geography, 16(3), 299-306. https://doi.org/10.1177/19427786231159357

(Original work published 2023)

[36] Radeck, M., & Khodakarim, A. (2022). Iran: the beginning of feminist

revolution. Horizon Insights, 1.

[37] Open Observatory of Network Interference. (2022, 11 29). Technical multi-

stakeholder report on

Internet shutdowns: The case of Iran amid autumn 2022 protests. Retrieved from OONI.org: https://ooni.org/post/2022-iran-technical-multistakeholder-report/#mobile-network-outages

[38] Radeck, M., & Khodakarim, A. (2022). Iran: the beginning of feminist

revolution. Horizon Insights, 1.

[39] Akbarzadeh, S., Naeni, A., Bashirov, G., & Yilmaz, I. (2024). The web of Big Lies:

state-sponsored disinformation in Iran. Contemporary Politics, 31(2), 328–

347. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569775.2024.2374593

[40] Akbarzadeh, S., Naeni, A., Bashirov, G., & Yilmaz, I. (2024). The web of Big Lies:

state-sponsored disinformation in Iran. Contemporary Politics, 31(2), 328–347. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569775.2024.2374593

[41] Reporters Without Borders. (2025). Iran. Rsf.org. https://rsf.org/en/country/iran